by Kornelija Koneska, Architect

The term “brutalism” comes from the French word “béton brut”, meaning “raw concrete”, which reflects the predominant material used in this architectural style. Emerging after World War II, brutalist architecture aimed to establish a powerful and raw aesthetic, often characterised by massive concrete structures, geometric shapes, and a utilitarian approach.

Brutalist architects sought to create buildings that were honest and straightforward in their design, showcasing the raw materials and structural elements. The functionalist philosophy behind Brutalism argued that a building’s form should follow its function, with an emphasis on practicality, efficiency, and usability.

In terms of spatial planning, Brutalist buildings often feature large, open interior spaces that can be easily adapted for various uses. The design typically emphasizes functionality, with an emphasis on providing clear circulation paths and easily accessible amenities.

Furthermore, the exposed concrete surfaces used in Brutalist architecture are often left untreated, revealing the construction process and showcasing the building’s structural elements. This approach is an expression of the functionalist philosophy, as it demonstrates an honest representation of the building’s materials and construction techniques.

Brutalist architecture also tends to prioritise the integration of buildings with their surrounding environment. Many Brutalist structures incorporate landscaping and green spaces to create a harmonious relationship between the built environment and nature.

While Brutalist architecture has often received criticism tor its stark appearance and perceived lack of aesthetic appeni, proponents argue that its functionalist approach is a response to the need for practical, efficient, and purpose-driven design. By focusing on function and prioritising the needs of the users, Brutalism sought to create buildings that were responsive to their intended use and provided a sense of honesty and integrity in their design.

Skopje’s embrace of brutalism resulted in a cityscape that captures the spirit of this architectural movement. Thanks to visionary designs, epitomised by the plan of the city center designed by the famous Japanese architect Kenzō Tange, Skopje has become one of Europe’s most interesting architectural landmarks.

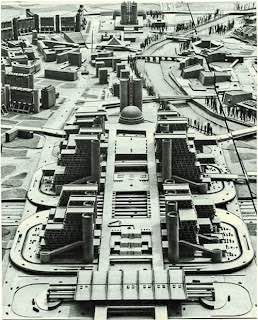

‘Plan for Skopje 1963’

was the urban and architectural plan put forward to rebuild the city of Skopje following the 1963 earthquake. The plan was developed between 1963 and 1966 by the government of Yugoslavia and the United Nations.

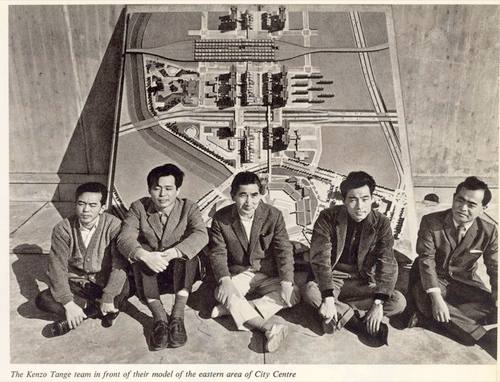

The rebuilding of the city attracted wide international attention which led to the involvement of a high architects. Along with several Yugoslav and international architecture teams, the UN invited Kenzō Tange and his team to participate in an international competition for the urban design of the city center in 1965. Architects that participated in the plan included Greek architect Constantinos Doxiadis, Polish architect Adolf Ciborowski and Dutch architects Van den Broek and Jaap Bakema. Other architects included Luigi Piccinato (Italy) and Maurice Rotival (USA). Yugoslav participants included Slavko Brezoski, Aleksandar Djordjevic, Edvard Ravnikar, Radovan Miscevic, and Fedor Wenzler.

The plan is unique in its architectural focus involving a holistic approach combing Metabolism, Brutalism, and the Architecture of Yugoslavia and culturally relevant due to international attention and collaboration backed by the UN – a rare example of Cold opinions among locals and visitors War unity between 20th century alike. superpowers.

The architectural plan has been revisited, theorised and discussed due to its impact on Brutalist architecture and 20th century art history. The impact of the plan affected the urban, historical, and cultural direction of the Yugoslav society. The implementation of the reconstruction of Skopje is a historically unique instance of UN international collaboration, it is also the first example of Japanese architects implementing Metabolist theory and modern architectural methods on a metropolis-scale urban project outside of Japan.

A Bold and Controversial Identity

Skopje, the capital city of North Macedonia, is renowned for its unique and distinctive architectural landscape. Among the various architectural styles that have left their mark on the city, one stands out prominently – Brutalism. Brutalist architecture in Skopje has not only shaped the city’s skyline but has also sparked debates and polarized opinions among locals and visitors alike.

As stated above, Brutalism was a response to the prevailing architectural trends of the time. Championing raw concrete as the architecture and 20th century art primary material, emphasising functionality, honesty, and a sense of monumentalism, Brutalism found fertile ground for expression in Skopje following the devastating earthquake in 1963 that left the city in ruins.

However, the rise of Brutalist architecture in Skopje has not been without controversy. Critics argue that the starkness and heaviness of concrete structures clash with the city’s historic and more ornate architectural heritage. They claim that Brutalism neglects the human scale and fails to create a harmonious urban environment. Additionally, the often grey and austere appearance of Brutalist buildings has faced criticism for its perceived lack of warmth and inviting qualities.

Nevertheless, supporters of Brutalism in Skopje contend that the style’s unapologetic use of concrete serves as a reminder of the city’s tumultuous past and its ongoing struggle for progress. They argue that the grandeur and monumental presence of Brutalist structures command attention and convey a sense of stability and strength. Moreover, Brutalist architecture’s functionalist approach emphasises the prioritisation of function and purpose over aesthetics.

Following the earthquake in 1963, Skopje underwent a massive reconstruction. At the helm of this endeavour was the acclaimed Japanese architect Kenzō Tange, who envisioned a new Skopje that would be a testament to modernity and resilience. Tange’s design concept embraced the principles of brutalism, setting the stage for the transformation of Skopje’s architectural identity.

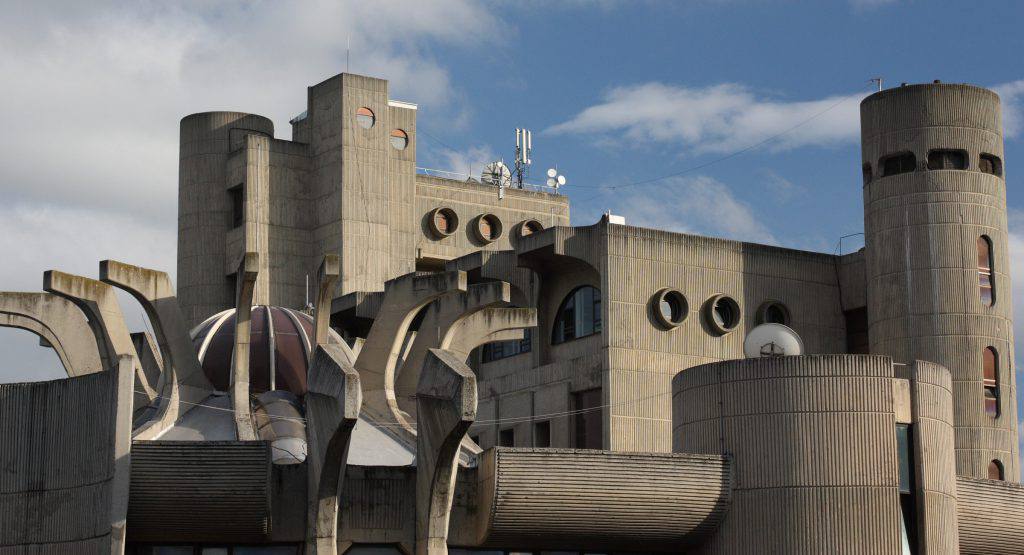

Telecommunications Center & Post Office HQ (PTT Center)

One of the most unique sights of Skopje, supremely bizarre and highly interesting Architect: Janko Konstantinov (with Dusanka Balabanovska, Lenka Janeva, Kostadinka Pemova and Mimora Kapsarova)

Years of construction: 1972-1989

One of the most iconic structures that emerged from this era is the Telekom Building, designed by Janko Konstantinov. Its colossal concrete form, featuring a distinctive pattern of rectangular openings, stands as a striking testament to da brutalist style.

The building’s austere exterior belies the modern telecommunications infrastructure it houses within, emphasising the utilitarian nature of brutalism. This colossal structure immediately luminary captures attention with its massive concrete facade and geometric patterns. It symbolises the aspirations of a modern and technologically advanced society. The Telekom Building’s bold design reflects the confidence and ambition of Skopje as it sought to rebuild and redefine itself in the aftermath of the earth quake.

Skopje’s embrace of brutalism is not limited to grand public buildings; the city’s residential complexes also reflect this architectural style. Blocks of apartment buildings, such as those found in the city center (City’s wall) and Karposh neighborhood, showcase the utilitarian and geometric characteristics of brutalism. With their raw concrete facades and repetitive patterns, these housing complexes evoke a sense of order and functionality. While brutalism has had its fair share of critics who argue that its austere and imposing structures lack warmth and human scale, Skopje’s brutalist architecture tells a unique story of a city that rose from the ashes of destruction. It stands as a testament to the resilience of its people, who embraced a bold and uncompromising architectural vision to rebuild and redefine their urban landscape.

Today, Skopje’s brutalist architecture continues to be a source of fascination for architects, historians, and tourists alike. It serves as a living museum of a bygone era, capturing the spirit and ethos of the brutalist movement. Whether admired or debated, Skopje’s brutalist structures have left an indelible mark on the city, embodying its history, aspirations, and the boldness of architectural experimentation.

Other Modernist buildings in Skopje build after the urban and architectural plan for Skopje 1963:

- Transportation Centre Skopje (completed in 1981) by Kenzō Tange

- Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi Elementary School (1967-1969) funded by Switzerland and CIAM luminary Alfred Roth

- Museum of Contemporary Art (1969-1970) funded by Poland designed by Jerzy Mokrzynski, Eugeniusz Wierzbicki, and Waclaw Ktyszewski

- Military Hospital (1969-1971) by Josip Osoynik and Slobodan Nikolic, architects of the Military Medical Academy in Serbia

- University Campus (1970-1974) by Slovenian Marko Music

- Cultural Centre (1968-unfinished) by Biro 71

- Macedonian Academy of Sciences and Arts by Boris Cipan

- City Commercial Centre (1981-1983) by Zivko Popovski learned from Dutch architects Van den Broek and Jaap Bakema

- Post Office, a brutalist masterpiece by Janko Konstantinov

- Goce Delcev Student Dormitory by Giorgi Konstantinovski

- City Archives, Skopje by Giorgi Konstantinovski

- State Hydro-meteorological Institute (1972-1975) by Krsto Todorovski

Maintenance and support for these buildings waned after the fall of Yugoslavia. At the start of the 21st century, all of the architectural progress encapsulated by these buildings was reversed by the Skopje 2014 project.

More information: https://www.SpomenikDatabase.org

The original article was published in Target Global

Leave a comment